- Published on

Programming Chess Engines Part 2

- Authors

- Name

- Henry Li

- https://x.com/yellowdragoon1

Part 1: The Game Representation can be found here

This part of the Programming Chess Engines series focuses on search algorithms. Let's start with a brief primer on what we have so far:

Background

Assume that we have a functional board representation, complete with functionality for common methods such as:

- Enumerate all legal moves in a position

- Make/unmake a move on the board

- Check for end states (checkmate, stalemate, repetition)

This is the backbone of our chess engine, but now we must fill in the brains, which allows the engine to input a position and output the objectively best move.

Conceptually, the task is very easy to understand, but in practice it's very difficult. Why is that? The goal is for us to answer that question by the end of this article. Without further ado, let's dive straight into the basics of search algorithms.

Part 2: Search and Evaluation

The Basics: Minimax

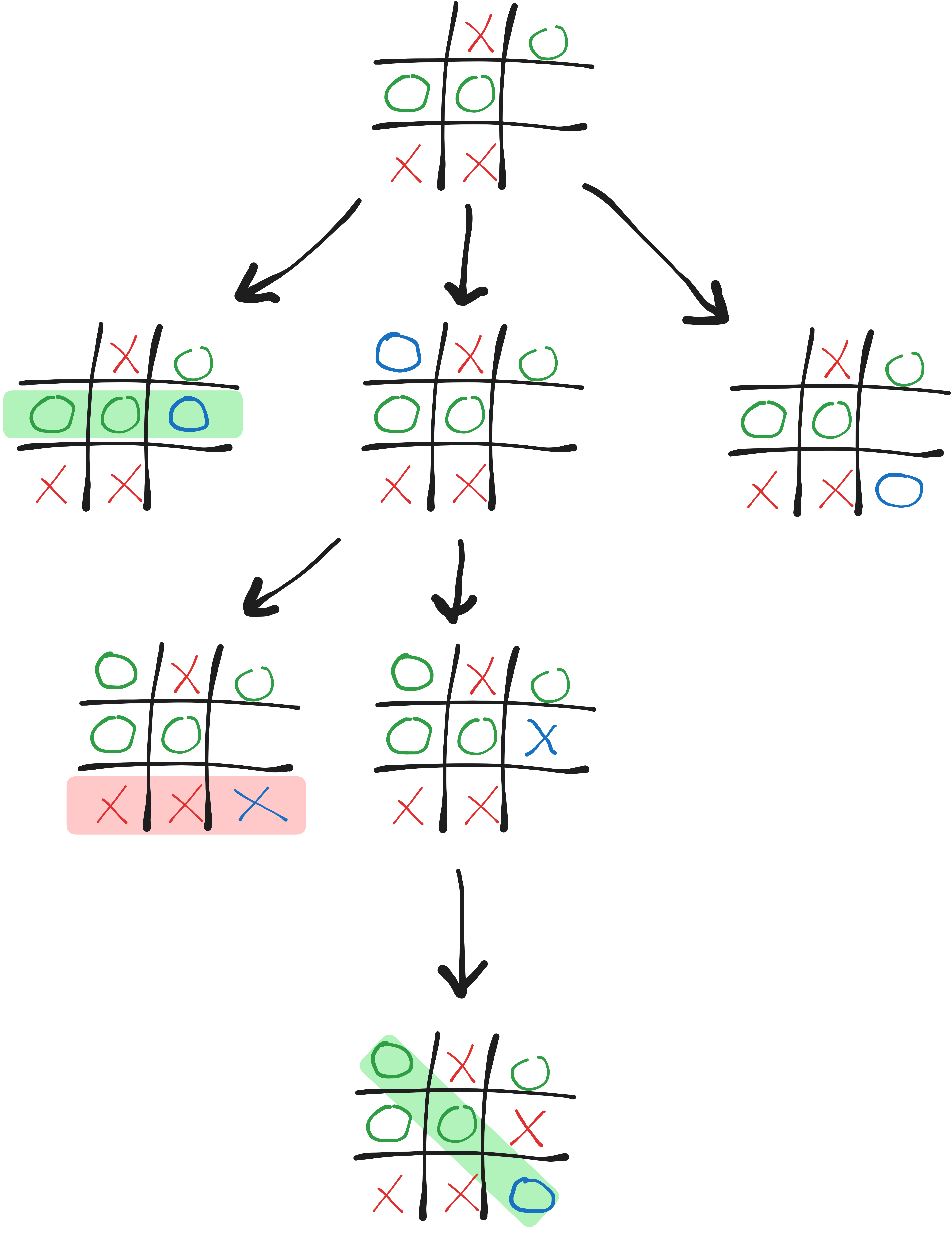

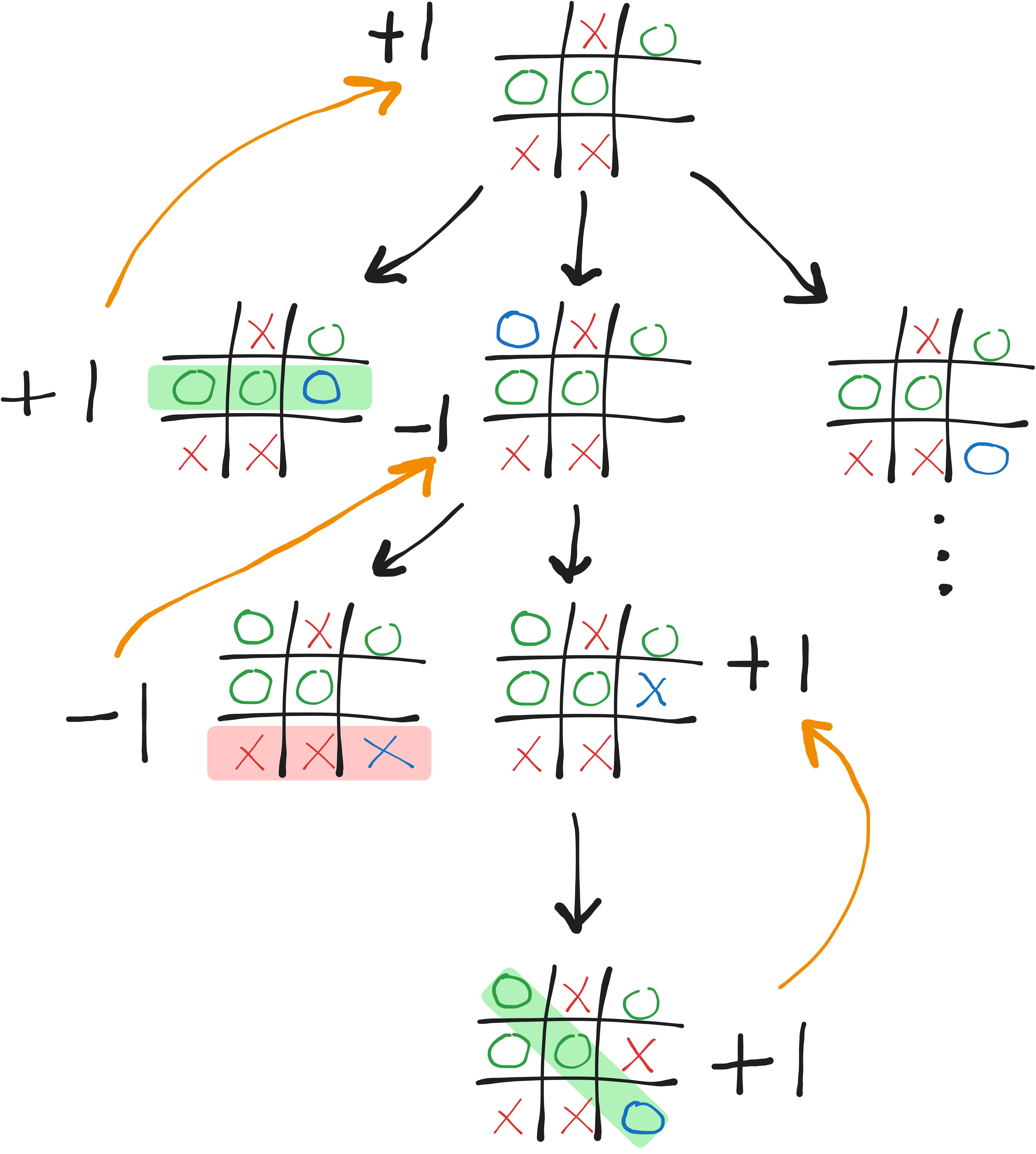

Given a chess position, how do we find the best move? If we had infinite computing power, the answer to this question would be to brute-force every possibility in the game tree until a terminal state is reached, and to use this information to make a decision. Here's the common example of tic-tac-toe to illustrate how this strategy works in practice:

When we get to a terminal state, it makes sense to assign that state a score, for example:

- Win: +1

- Draw: 0

- Loss: -1

We can now propagate this score up the game tree to the root node, or our current position. If it is our turn to move and we can win the game with a certain move, then the score for the position should be +1, since we've looked ahead to know we can reach the winning position. This process works recursively.

The main catch to be aware of is that we must evaluate the position from the opposite perspective every time we propagate scores up the tree, since a +1 score for us is actually a -1 score from the perspective of the opponent. Practically speaking, this just means reversing the signs of the scores on every recursive evaluation. The score of a position is evaluated as the best score (from the perspective of the current player) a move can return.

And that's all there is to the rudimentary search algorithm known as minimax! The name is derived from the fact that player A is trying to maximize the score and player B is trying to minimize the score (remember, +1 means win, -1 means loss).

It's time to build upon this foundational strategy to improve on minimax, but first, we must answer the question: why does naive minimax not work for chess?

Branching Factor

For a simple game like tic-tac-toe, minimax works perfectly because we can brute force every possibility to the end of the game. The game can only be 9 moves long at most, and for each move there is a maximum of 9 possible moves. Furthermore, the number of possible moves reduces by 1 every turn, so this naturally leads us to 9! = 362,880 possible positions—though in reality games can end early, so the true number is 255,168 (according to stackexchange). The branching factor for a game tree refers to the number of possible options for every move. The larger this factor, the more the search space will explode as the number of moves grow. Usually, this number is not fixed, so we compute or approximate the average branching factor of the game. For tic-tac-toe, this number is around 4, which is very low. Coming back to chess, the average branching factor is 35. Coupled with the fact that the average game length is around 70 moves, it is clear that brute force is computationally infeasible.

35^70 = More than the number of atoms in the observable universe! (By ~27 zeros)

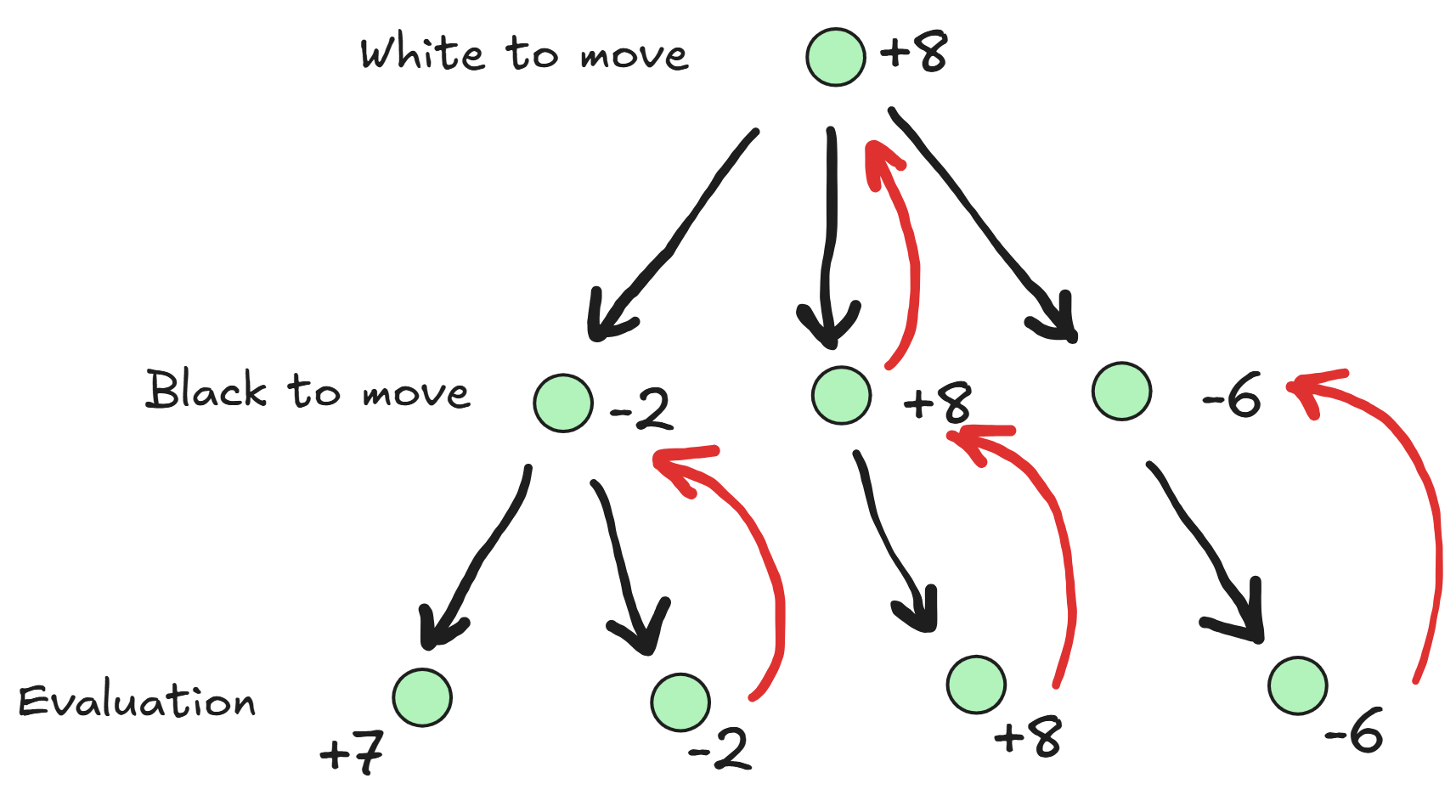

In order to not have to evaluate the entire game tree, we have to be able to assign scores to non-terminal positions, which segues into our next topic.

Evaluation

The simplest evaluation function assigns scores to each piece type and adds up the total score for both sides. The difference between these scores is the evaluation of the position. A concrete example:

- Queen: 9

- Rook: 5

- Knight/Bishop: 3

- Pawn: 1

White: 1 Queen, 1 Rook, 3 Pawns = 9 + 5 + 3(1) = 17

Black: 2 Bishops, 2 Knights, 7 Pawns = 2(3) + 2(3) + 7(1) = 19

17 - 19 = -2 (from White's perspective), or +2 (from Black's perspective)

Now in our minimax search, we can set a maximum depth to look ahead, and after this depth is reached we stop, evaluate and assign the evaluation score to the position. We can then propagate the scores back to the root position as before. An illustrative example:

This allows us to constrain our search to a manageable depth, but now that we are not searching the entire game tree, our evaluation of the position is no longer 100% accurate, since we are only using a heuristic to estimate the value.

Optimizations to this algorithm have driven chess engine development for the last 50-60 years, culminating in the well-known Stockfish. Only in the last 5-10 years have we moved on to a new paradigm using Neural Networks and Deep Reinforcement Learning with the rise of DeepMind's AlphaZero. For now, we will leave the state-of-the-art discussion for a future article.

There are broadly 2 classes of improvements we can make to the minimax algorithm:

- Search: to search more positions in the same amount of time, or to search in a more efficient way

- Evaluation: to improve the evaluation function, giving us a more precise estimate of the true value of the position

Search Improvements

Alpha-Beta Pruning

The first improvement we'll discuss is a modification to the minimax depth search. The idea of alpha-beta is to avoid searching large unnecessary parts of the game tree. The essence of this algorithm can be demonstrated with the following example:

- We are considering 2 moves for White, move A and move B

- After fully evaluating move A, we give it a score of +3

- We start evaluating move B. We find that Black has a response which leads to a score of +1

- We can immediately stop looking for any more of Black's responses to move B! We already know that move A is better than move B because Black is guaranteed to obtain a score of +1 (or better) versus the guarantee of +3 for White in move A

Therefore, we can 'prune' the search of move B early, without losing any accuracy. The alpha and beta values represents the best score that each player is guaranteed so far, and by keeping track of these 2 values during search we can prune many branches of the search tree.

Using alpha-beta, we can reach a much higher search depth with the same compute power, thus improving the engine's accuracy.

Move Ordering

When evaluating moves using alpha-beta, the order in which we consider moves matters a lot. If we can start by evaluating the best moves in a position, we can quickly prune the game tree since we already have an accurate alpha or beta heuristic.

There are many techniques and heuristics that can be used to try evaluate the best moves first. Some of the most well-known are:

- MVV-LVA: priority is given to least valuable pieces capturing most valuable pieces

- Killer Heuristic: we remember moves that caused a pruning in alpha-beta search in sibling subtrees, as these moves are likely to have high impact on the position

- Hash Move: transpositions are a very commonplace occurrence during search, where the exact same position arises from a different move order. To avoid having to evaluate the same position many times, we can store a hash table from position to evaluation and perform a quick lookup before search to check if we already have a stored evaluation for that position

The Horizon Effect

One issue we can run into with limited depth search is that the evaluation function fails to consider dynamic factors in the position. Consider a position where we can capture the opponent's queen, leading to a 9-point evaluation swing! If we terminate the search there and add up all of the piece scores, we will have grossly underestimated the true value of the position. This the major downside of having a fixed search depth or horizon.

To account for the horizon effect, we can slightly modify the algorithm to keep searching even after the fixed depth is reached until there are no more forcing moves (captures, checks, promotions). This modification is referred to as Quiescence Search.

Iterative Deepening

Chess engines don't have infinite time to run a large-depth search. How we do know what depth to bound our search? If it's too small, our engine will not be as strong as we want. If it's too large, our engine will take forever to generate a move.

One way of handling this problem is to start with the lowest-depth search, and once this is completed, we search again at 1 higher depth, and so on, until we run out of our allotted search time. When this happens, we can simply select the best move from our most recent, deepest search. To illustrate:

- Depth 1, best move: X

- Depth 2, best move: Y

- Depth 3, best move: Z

- Depth 4, out of time

In the above scenario, we will choose move Z, since it is the deepest search we successfully terminated.

Principal Variation

One advantage of iterative deepening is that we can use the best move sequence or principal variation (PV) from a lower depth to inform our move ordering for the higher depth. For example:

- Depth 2: best move for White is move X, then best response from Black is Y

- Depth 3: prioritize looking at moves X/Y, since they were best in depth 2

Surprisingly, dynamic move ordering heuristics such as PV that are enabled by iterative deepening are so effective that it's actually more efficient to use iterative deepening rather than searching directly at the high depth!

With our search improvements complete, we can now discuss improvements in the evaluation function, which gets a much more concise treatment as the complexity mostly stems from domain-specific knowledge rather than interesting algorithms or techniques.

Evaluation Improvements

Going beyond the basic evaluation function of adding all of the piece values, we can start to build a hand-crafted evaluation (HCE) function, which also takes into account many other aspects of the position. It is common to take a linear combination of the different features to calculate the final evaluation. I'll briefly mention some of these features below:

Piece-Square Tables

In chess, a common heuristic is to place your pieces in the center of the board, since they tend to have stronger mobility and power in the centralized position. However, the King should be away from the center and towards the edge since it is the most vulnerable piece. Bishops are long-range attackers so they can be effective from the edge whereas Knights are the opposite. Such piecewise heuristics can be encoded by adding a modifier to each piece's score depending on the location on the chessboard. This should give us a slightly better estimate of the value of the pieces.

Mobility

The more possible moves a piece has, the more effective it is at controlling the board. We can account for this by rewarding pieces/positions with high mobility and penalizing low mobility.

King Safety

Reward positions where the king is shielded by our own pieces, and penalize positions where the king is open/attacked by many enemy pieces.

Space

How many squares on the chessboard does our pieces control? The higher this number, the better our position is likely to be, since having more space translates to better piece maneuverability and opportunities for attack/exploitation.

Conclusion

The combination of a meticulously hand-crafted evaluation function and a highly optimized search algorithm has culminated in the Stockfish chess engine (amongst many others). This brings us roughly to the state-of-the-art from about 5-10 years ago.

A note to the curious: while I've covered many of the fundamental building blocks of the modern chess engine, there are still many improvements and techniques that I have not mentioned. My goal here is to help you understand the essence of the main ideas, so you have the prerequisite knowledge to jump into any further techniques. If you are curious, I'd encourage you to explore the Chess Programming Wiki for much more detailed information.

Thank you for sticking until the end! I'll see you in part 3, where I'll talk about the latest advancements using Neural Networks and Deep Reinforcement Learning.